- © 2025 Annapolis Home Magazine

- All Rights Reserved

In the previous two publications of Annapolis Home, we established a geological and cultural baseline of history for the Chesapeake Bay. We framed an argument for the need to increase its protection and preservation. Centering this argument is a crucial fact: The Bay is uniquely fragile. Its shallow waters and the creatures living within are influenced by flows, temperatures, tides, pollution, chemical discharge, overfishing, and much more. Each of us has a responsibility to protect it.

SO WHAT IS BEING DONE?

The answer could be “a lot” or “not enough” or “why does it matter?” depending on one’s perspective. In one small tributary of the Chesapeake Bay, several designers, environmentalists, and engineers are working especially hard. Over the past several years, dozens of projects have focused on improving the overall health of Spa Creek. These projects included design professionals, conservancies, philanthropists, lawmakers, concerned citizens, and volunteers collectively working together. From the headwaters all the way to the mouth of the creek, change is happening.

This Regenerative Stormwater Conveyance device, created by Biohabitats, stores water in the soil and in step pools, allowing it to slow down and release contaminants before entering Spa Creek.

Headwater Projects

The Spa Creek Conservancy recently embarked on a bold undertaking to restore the upper headwaters of Spa Creek. They began with a grant, managed by the Center for Watershed Protection, to assess the watershed for its health and environmental needs. Reports and plans for action were developed for both tidal and non-tidal areas. Biohabitats, an environmental design firm headquartered in Baltimore, was engaged to help design, permit, and manage construction of the restoration.

In 2015 a grant was awarded to Spa Creek Conservancy through the Chesapeake and Atlantic Coastal Bays Trust Fund. This project will help fulfill mandates set forth by Chesapeake watershed states to reduce total nitrogen, phosphorus, and suspended solid levels by 2017 and 2025. After years of planning, community dialogue, and permitting, the work commenced in May and is estimated to take ten months to complete.

With an interest in seeing the construction in action, I walked the project with Joe Berg from Biohabitats. Our first stop was the removal of invasive grasses called Phragmites australis in the lower headwaters. Large machines delicately navigated raised berms to access the Phragmites. They were dug out, removed, and dried before being hauled offsite to a controlled fill site. In their place, coir fiber logs and sand were installed to raise the water to suitable depths so native grasses and intertidal marsh plantings could thrive.

Fish Rescue

Our second stop was upstream of the Phragmites removal area, where heavy erosion had occurred over time. Water levels at the bridge and culvert under Spa Road at the Department of Public Works building historically flowed upstream through the culvert pipes. In recent years, however, constant erosion below the bridge lowered stream levels to 18” below the pipe, thus blocking tidal flows and preventing fish from swimming upstream. Biohabitats creatively solved this issue by installing a series of “riffle grade control” measures within the stream. Each grade control consisted of an incline of large and small stones that raised the grade 6″. These inclines resulted in the creation of larger pools of water, adding storage volume and further protecting the stream against large storm events. With five controls in place, water level was raised back up through the culvert pipe, allowing fish to once again reach an upstream marsh.

Helpful Beavers and Biomimicry

Our third stop was located above the Spa Road bridge in a freshwater marsh inhabited by beavers. During the lengthy design and permitting process, Biohabitats studied this marsh. They found that beavers had built elaborate dams that in turn had helped to control water flows and increased storage capacity in the stream. During large storms, however, these dams would succumb to water velocity and pressure. In response to these naturally occurring events, Biohabitats used the science of biomimicry to design stronger “dams” using woven willow branches. These dams will be placed at strategic locations in the next several weeks and will act as more permanent erosion control measures against future storms.

We finished our tour in the backyards of the Southwoods community where one lonely stormwater pipe marks the beginning of the stream. In this narrow landscape, heavy storm flows create erosion and scour out acid sulfate soils, in turn creating gray waters that are harmful to fish and wildlife. Using the same riffle control measures, Biohabitats intends to slow water flows and increase storage at each step pool, effectively managing the flow of water back to the source off the creek.

Native plants in this Spa Creek garden need little maintenance and attract abundant wildlife in the form of birds, bees, butterflies and other organisms.

Neighborhood Activists

While a lot of work is happening in the headwaters of Spa Creek, change is happening in the surrounding neighborhoods as well. Homeowners are planting trees, shrubs, and native groundcovers and improving their properties through conservation landscaping. City requirements that limit impervious or hard surfaces and require plantings are guiding homeowners to create larger green spaces and healthier native gardens. Civil engineers and landscape architects are designing stormwater systems that manage runoff on individual properties rather than pushing problems onto neighboring properties, or worse, into the creeks and rivers. Local landscape architect Vernon Husted has designed roughly 40 of the dozens of projects that have occurred over the last 10 years, and has helped the community to install 22 of them (many through grant applications). According to Vernon, the success of these project is not simply the protections put in place, but also the community energy, support, and education that results from collective purpose.

At one residence along Spa Creek, Campion Hruby worked with the homeowners to create a waterfront garden teeming with wildlife. Throughout the project several environmental measures were considered. Large stately trees on the waterfront slope were treated and protected. Lawn and invasive phragmites were removed from the waterfront yard and along the water’s edge. In place of invasives, the owners planted a diverse collection of native plants. As an avid birder, the owner wished to create a landscape that would support several species of birds and other wildlife. Today, the owner shares the thrills of seeing various birds, butterflies, bees, and other pollinators with his two young daughters.

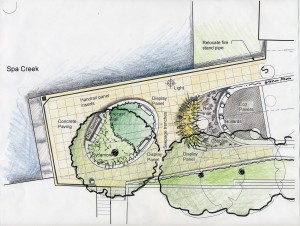

A large bioretention garden planned for SAYC will clean dirty water from rooftops and parking lots before it enters Spa Creek.

Mouth of the Creek

At the wider waters along the mouth of the creek, business owners, engineers, architects, landscape architects, and environmentalists are working on several projects that will help the Bay survive.

Landscape architect Jim Urban has worked on several projects focused on progressive stormwater management and tree preservation. At the end of 4th Street in Eastport, Jim worked with the TKF Foundation to transform a street-end park into a functioning rain garden that captures rainwater and uses it to water nearby trees and native plants. The site also provides a public space for gathering and a historical marker of the location of the old bridge between Eastport and Annapolis.

Nearby at the South Annapolis Yacht Center, plans are developing to rebuild the stormwater infrastructure in a way that greatly improves pollution and runoff issues. For every inch of rain that falls during a single storm, more than 60,000 gallons of unmanaged stormwater currently flow into Spa Creek. This massive amount of unfiltered runoff is dangerous to the Creek. The new designs will manage large and small storms through bioretention, rain gardens, green roofs, and pervious (or absorbent) paving techniques.

Collective Action

These are simply a few of many projects happening on one creek. Spa Creek is a microcosm of how compounding small changes can make a larger impact. On both small and large scales, this waterway is being changed by people who care about the future of our environment.

But change is happening everywhere. Progress is being made on creeks and rivers up and down the Chesapeake Bay. As a landscape architect and a concerned citizen in the community, it has become clear to me that a healthy Chesapeake Bay won’t happen unless we all keep moving in a common direction. Large ambitious projects are wonderful, but they are often few and far between. The change we envision for the Bay will only happen if we take advantage of all opportunities to make a difference, on both large and small scales, in both public and private settings. At a time when environmental regulations are threatened, we must be the change that we want to see happen. We cannot leave it up to others.

So get on the train folks! Good things are happening everywhere but we need to do more and at every chance we get. Be informed. Get involved. Be a part of a better future for the Bay.

RESOURCE

Campion Hruby Landscape Architects, campionhruby.com

Kevin Campion has lived in the Chesapeake Bay watershed his entire life. He and Bob Hruby own Campion Hruby Landscape Architects in Annapolis, Maryland. Kevin earned a bachelor’s degree in landscape architecture at Penn State University, and a Master of Philosophy with a focus in landscape conservation from the Edinburgh College of Art in Scotland. He is a registered landscape architect in the state of Maryland and an active member of the American Society of Landscape Architects.

Annapolis Home Magazine

Vol. 8, No. 4 2017