- © 2025 Annapolis Home Magazine

- All Rights Reserved

The United States Naval Academy is an extremely rare example of multiple buildings and their setting all designed in the American Beaux Arts style. New York architect Ernest Flagg conceived the campus and all the buildings surrounding the quadrangle in 1902. The architectural principles of the Beaux Arts contrast sharply with the Baroque concepts used by Sir Francis Nicholson when he planned the town of Annapolis in 1694. These very different approaches were described in Part 1 of this series. This installment examines the specific character of American Beaux Arts architecture.

American architecture between 1890 and 1920 was dominated by the buildings of architects schooled in Paris at the École des Beaux-Arts. The historic U.S. Naval Academy campus is the perfect place to experience the stylistic features of American Beaux Arts architecture. The buildings have strict symmetrical lines centered on the front entrance, deeply grooved masonry, a main entrance elevated above the ground, and architectural elements referring to the Roman Empire. The creative use of lush decorative trims, moldings, cornices, and other highly detailed architectural features are fully integrated into the architectural composition, not added on later as afterthoughts.

American architecture between 1890 and 1920 was dominated by the buildings of architects schooled in Paris at the École des Beaux-Arts. The historic U.S. Naval Academy campus is the perfect place to experience the stylistic features of American Beaux Arts architecture. The buildings have strict symmetrical lines centered on the front entrance, deeply grooved masonry, a main entrance elevated above the ground, and architectural elements referring to the Roman Empire. The creative use of lush decorative trims, moldings, cornices, and other highly detailed architectural features are fully integrated into the architectural composition, not added on later as afterthoughts.

The impact of French architectural education on American building cannot be overstated. The New York Public Library, Grand Central Station, the Library of Congress, Union Station in Washington, D.C., and Penn Station in Baltimore are just a few buildings designed by École-trained architects. The Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1892, the World’s Fair of its day, began the nationally popular run of American Beaux Arts architecture that lasted until the Great Depression of 1929.

Formal training for architects in America was not available until the Massachusetts Institute of Technology opened a program in 1865. Most architects learned the art by apprenticeship or mastering a building trade. The finest architectural school in the world during the nineteenth century was the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In 1846 Richard Morris Hunt became the first American to attend the school. Hunt was an extremely successful architect, designing the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Breakers and Marble House mansions in Newport Rhode Island, and the Biltmore estate for the Vanderbilt family. The first wave of American architects trained at the École included Henry Hobson Richardson and Charles McKim of the architecture firm McKim, Mead & White, among many others. The second wave included every American architectural candidate that aspired to first tier status in the profession. Among the second wave was Louis Sullivan of Chicago and Annapolitan architect T. Henry Randall (1862–1905) who worked for McKim, Mead & White and then opened his own office in New York. Earnest Flagg attended the École from 1889 to 1891. He was devoted to École architectural principles his entire career, which culminated in the design of the buildings and campus of the Naval Academy.

Many Beaux Arts buildings remain throughout the country, but only a few examples of Beaux Arts urban planning survive. The Chicago Columbian Exposition plan was a tour de force in Beaux Arts urban planning. Monumental with broad vistas to symmetrical buildings created a popular sensation and inspired the City Beautiful movement. The Exposition buildings were destroyed, as planned, shortly after the fair closed. An excellent existing example of grand scale Beaux Arts city planning is the National Mall in Washington, D.C., which was redesigned in 1901 by architect Charles McKim. The U.S. Naval Academy campus remains a rare environment with multiple buildings and urban planning using Beaux Arts architectural principles.

Many Beaux Arts buildings remain throughout the country, but only a few examples of Beaux Arts urban planning survive. The Chicago Columbian Exposition plan was a tour de force in Beaux Arts urban planning. Monumental with broad vistas to symmetrical buildings created a popular sensation and inspired the City Beautiful movement. The Exposition buildings were destroyed, as planned, shortly after the fair closed. An excellent existing example of grand scale Beaux Arts city planning is the National Mall in Washington, D.C., which was redesigned in 1901 by architect Charles McKim. The U.S. Naval Academy campus remains a rare environment with multiple buildings and urban planning using Beaux Arts architectural principles.

The main entrance façade of Bancroft Hall faces the park-like quadrangle, and is directly aligned with the entrance of Mahan Hall. Beaux Arts architects were well trained in the creation of architectural ornamentation. Note the battleships plowing out of the Bancroft Hall roof parapets. This ornamentation is not a slavish copy of classical architectural details, but a wholly unique creation explicit to this building.

Beaux Arts architects were also trained to create specific unique floor plans for the building functions. They itemized the needs of the users, identified functional adjacencies, and applied principles of circulation to create distinctive site-specific floor plans intended to function practically and efficiently. While all of Flagg’s Naval Academy buildings have been modified or expanded, the original primary interior spaces are intact and continue to function with efficient grace.

Mahan Hall was designed as the main classroom building. It includes many features of Beaux Arts architectural principles. The symmetrical entrance is raised a floor above grade with a bold double staircase. The entrance axis is further emphasized by the clock tower, cupola, and segmented round pediment. Sculptures of allegorical figures, repetitive arches, and a variety of pediments, brackets, and balustrades complete the complex yet tightly controlled composition. Note the wonderful architectural hardware and lighting designed with nautical motifs.

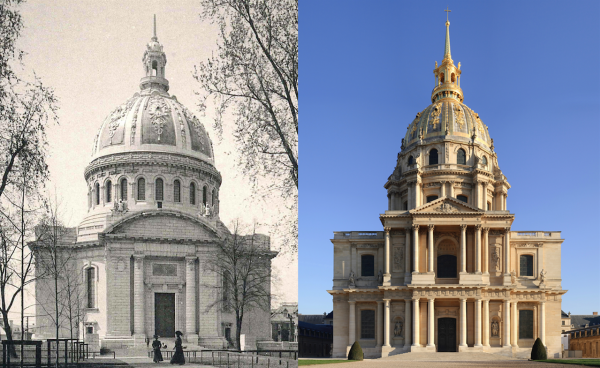

In the original 1908 construction, the Chapel dome was sheathed in highly ornate glazed terracotta with naval military symbols. Flagg warned the contractors of their failure to provide proper waterproofing for the dome. This resulted in the eventual failure of the terracotta ornament, and its replacement with the copper roofing we see today.

In the original 1908 construction, the Chapel dome was sheathed in highly ornate glazed terracotta with naval military symbols. Flagg warned the contractors of their failure to provide proper waterproofing for the dome. This resulted in the eventual failure of the terracotta ornament, and its replacement with the copper roofing we see today.

The U.S. Naval Academy Chapel is a masterpiece of American Beaux Arts architecture. Flagg placed it on the highest ground and central to the entire campus composition. The dome is based on the design of the 1708 Royal Chapel at Les Invalides in Paris, designed by architect Hardouin Mansart. There are two very interesting parallels here: the Royal Chapel contains the 1840 bombastic imperial burial site of Napoleon while the Naval Chapel contains the crypt of John Paul Jones, father of the American Navy. Jones’ crypt was built in 1913 with a design inspired by Napoleon’s tomb, much more modest but still impressive. The second parallel: the Baroque Royal Chapel was designed and built at the same time that Nicholson designed and built the Baroque urban plan of Annapolis. This is further evidence of how au courant the Annapolis town plan was in the world in 1694.

Chip Bohl is an architect, practicing in Annapolis

for 33 years. Visit www.BohlArchitects.com

From Vol. 4, No.6 2013

Annapolis Home Magazine