- © 2025 Annapolis Home Magazine

- All Rights Reserved

By Sherri Marsh Johns

Photography courtesy of Cloverfields Preservation Foundation and Annapolis Home

A team of professionals is collaborating to faithfully restore Cloverfields, a rare example of early 18th-century architecture tucked away on the Eastern Shore. Read on to learn about original owner Philemon Hemsley, formal terraced gardens, intriguing artifacts, and a host of architectural features not seen for hundreds of years. Cloverfields’ early restoration, sponsored by Cloverfields Preservation Foundation (CPF), is highlighted in Part One of this series. Part Two delves into the final restoration of the home and the resurrection of magnificent terraced gardens. Ground-penetrating radar helped inform architect and landscape architect Devin Kimmel’s formal design, whose plant list called for a spectacular 62,560 bulbs and 692 boxwoods.

William Hemsley (1736-1812) painted by John Hesselius.

In 1705, Philemon Hemsley (1670-1719), a wealthy planter and successful merchant, finished work on a house on the Wye River that was the envy of his Eastern Shore neighbors—the likes of which most native-born colonists had never seen. With approximately 300,000 bricks manufactured on site by skilled enslaved and indentured workers, Cloverfields was one of the largest houses of its time. Philemon was one of five children born to William and Judith Hemsley (1634-1685 and c. 1633-c. 1686), who emigrated in 1658 from England where they had lived secretly as Catholics. The Hemsleys quite possibly came to Maryland— then a proprietary colony owned by their fellow Catholic, Charles Calvert, third Baron of Baltimore—to escape the violent religious persecution and discrimination in Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan England.

Through architecture, the Hemsleys presented the world with a carefully crafted image of wealth and power, but the reality of life behind the grand façade was far more complicated. Letters describe family struggles with physical and mental illness—and medical treatments often more dangerous than the disease—all providing new insight into colonial life on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

Philemon’s grandson, William Hemsley (1736-1812) eventually inherited the house and engaged Philadelphia’s finest craftsmen to assist with redecorating Cloverfields in the highly fashionable Rococo

taste. More than sixty years passed before the grand Annapolis mansions of Brice, Paca, Ridout, and their wealthy cohorts surpassed Cloverfields in size and style.

Unfortunately, after William’s death in 1812, his descendants could afford little more than necessary repairs. When Cloverfields was sold outside of the family in 1897 to the Callahan family, the new owners consciously preserved the main dwelling by installing what then were considered modern amenities in a new rear wing. Thanks to the century-long stewardship of the extended Callahan family, when the Cloverfields Preservation Foundation (CPF) purchased the house in 2018, it remained in good repair and looked much as it had during the time of the Hemsleys.

CPF hired custom builder Lynbrook of Annapolis and Devin Kimmel of Eastport-based Kimmel Studio Architects to undertake the daunting task of restoring Cloverfields to its former Rococo glory when the family’s prestige had reached its apogee. Lynbrook and Kimmel were part of a specialized team led by building and landscape architect and veteran architectural historian, Willie Graham. A leading authority on restoration and building analysis, Graham has worked on many of the country’s most important historic buildings. The team collaborated with engineers, masons, historians, craftspersons, archaeologists, dendrochronologists, and even geophysicists, to determine how to resolve the structural problems threatening the building’s existence, and to develop a course of action.

More than three years later, work on Cloverfields is nearly complete and the 62,560 bulbs in the terraced gardens are in bloom. What Lynbrook president Ray Gauthier finds exciting is that during the restoration process, he observed master building techniques and meticulous craftsmanship that simply no longer exist. Striving to match these exceptional standards brought his own company to its highest level. “From the start, our mission has been to save as much original building fabric as possible and accurately recreate missing elements using traditional materials and techniques. We went into this with the mandate to carry out the work in a manner beyond reproach.”

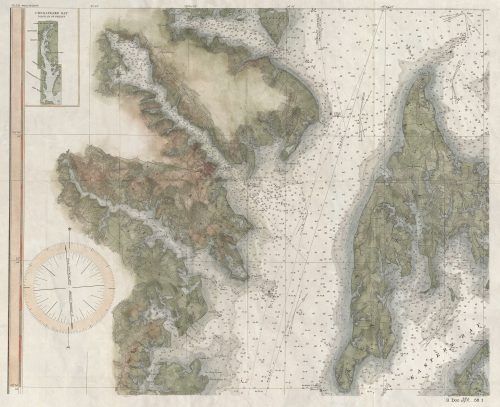

U.S. Coastguard 1895 soundings map.

Those fortunate enough to live near Annapolis may not immediately recognize the features that distinguish Cloverfields from other stately 18th-century mansions in the area, but upon closer inspection, superlatives come easily. First, Cloverfields is one of the oldest buildings in Maryland, firmly dated through dendrochronology (tree ring analysis) to 1703-1705. Second, it is one of the most intact houses from that period. Its many exceptional features include the oldest surviving staircase south of the Mason Dixon Line. Third, as a home built during the reign of Queen Anne, it was one of the first dwellings in the region to use classical details that would later become commonplace in Georgian architecture.

Architect Devin Kimmel explains, “one of the most significant contributions of Cloverfields to the history of American architecture is its classically-inspired cornice. Classical details were extremely rare in 1703-05 but would become commonplace soon after. So here we have an example of Cloverfields being ahead of its time in that sense, as a precursor of classical architectural details.” The second reason why the cornice is relevant is that “unlike its recent European counterparts, the cornice is integrated into the structure of the building. The structural quality proves that the cornice was planned from the outset. The cornice is, therefore, an experiment with both building methods and classical architecture.” Cloverfields was a leader, one of the first examples of how European classical details were adapted to the idiosyncrasies and experimental spirit of this side of the Atlantic.

Cloverfields’ extraordinary size, remarkable brickwork, and exceptional number of windows could not fail to impress a visitor in 1705. Many of Philemon Hemsley’s contemporaries endured Maryland’s relentless heat and bitter winters in something best described as a one-room wooden shack. Due to the cost and labor associated with brick, period builders often used wood in such unlikely places as fireplace chimneys (complete with a chain to pull it away in the not-unlikely event of fire). Even families with greater means routinely crowded together in houses measuring less than 500 square feet of space. Only wealthier households enjoyed a modicum of luxury that typically included a brick chimney, plaster walls, and a glazed window or two. It is in this humble context that Cloverfields’ comparative magnificence is best appreciated.

With two stories plus an attic and full-height cellar, totaling 6,998 square feet of space and a footprint of 8,022 square feet, Cloverfields presented as one of the largest houses in the Chesapeake. In an era when glazed windows were an expensive luxury and closets a novelty, Cloverfields was conspicuous for its thirty-three windows, including one inside each of the four closets. As late as 1798, well after William Hemsley had completed his expansion and remodeling, only one-fifth of rural houses were built of brick, two-thirds still had a footprint of 500 square feet or less, and glazed windows remained a costly option.

When asked what made Cloverfields special, the late renowned architectural historian and Annapolitan Orlando Ridout V listed more than a dozen unique or rare features, concluding, “You roll all that into one house, and it is a major icon of the early Chesapeake. Get the picture?”

When Applied Archaeology and History Associates Inc. conducted excavations in the cellar, they unearthed a slight depression where they found a range of items, including two different leather shoes, a horseshoe, pieces of glass, a single lead shot, and fragments of a variety of faunal remains. AAHA’s archaeologists believe this bundle, consciously placed beneath the cellar stair in the first half of the 19th century, may represent a form of African-American spiritual practice performed throughout the American South. Rooted in West African tradition, buried caches such as these represent a method by which African Americans preserved their cultural identity and expressed a subtle form of resistance.

The cellar bundle provides a reminder that, as with most colonial mansions, Cloverfields comes with a complicated past that includes a legacy of slavery. Enslaved craftsmen were essential in the building of Cloverfields, and for more than a century African Americans were compelled to carry out the onerous day-to-day work associated with plantation operations. William Hemsley’s letters express concern for the welfare of those he called his “black family.” At the same time, he naively voiced genuine surprise when four of his enslaved men ran away for what he deemed “no good reason.” The elder Hemsley’s view on slavery contrasted with that of his son, also named William, who found the practice morally insupportable and in his will freed the enslaved persons he had inherited. Cloverfields’ historian has discovered the names of many of the enslaved individuals and families who lived at Cloverfields, and CPF is committed to recognizing their contribution and honoring their legacy.

PROJECT MANAGEMNET AND RESTORATION: Lynbrook of Annapolis, lynbrookofannapolis.com, Annapolis, Maryland

ARCHITECTURE AND LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE: Kimmel Studio Architects, kimmelstudio.com, Annapolis, Maryland

To learn more about the Cloverfields Preservation Foundation and its team of professionals, visit cloverfieldspreservationfoundation.org

Sherri Marsh Johns is the founder of Retrospect Architectural Research and a member of the Cloverfields Preservation team.

A subsequent story will focus on the completed restoration and landscape, currently in progress, with McHale Landscape Design in charge of the installation.

Annapolis Home Magazine

Vol. 12, No. 3 2021